The other day, someone was talking to me about my series on biases in judgment and decision-making and it made me realize that I was missing a rather important bias — the contrast effect! I’m not sure how this one slipped through the cracks, but I’m glad to be able to write about it for you today.

The other day, someone was talking to me about my series on biases in judgment and decision-making and it made me realize that I was missing a rather important bias — the contrast effect! I’m not sure how this one slipped through the cracks, but I’m glad to be able to write about it for you today.

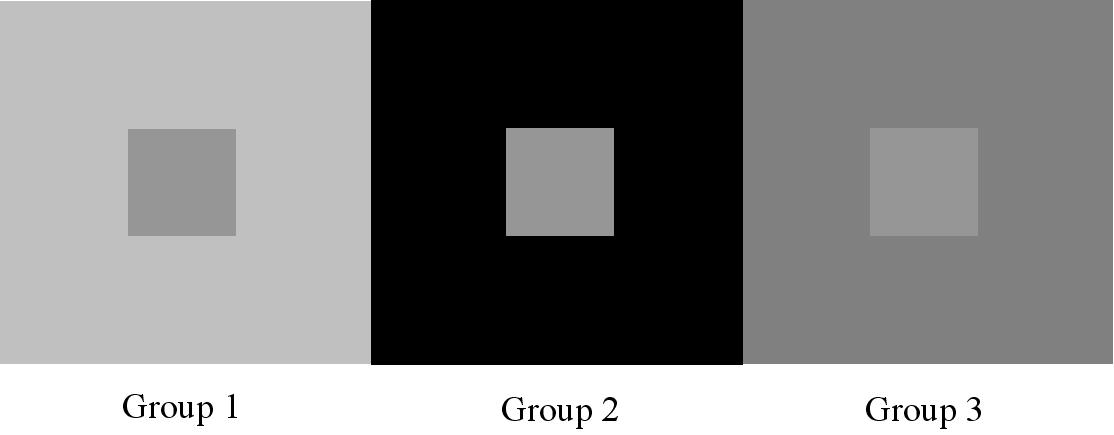

It’s been almost a year and a half since I wrote something for this series, so let me refresh your memory. Each week, I took a cognitive bias and explained it. I provided an example and then I offered some ways for mitigating that cognitive bias in your own life. So, without further adieu, the contrast effect.

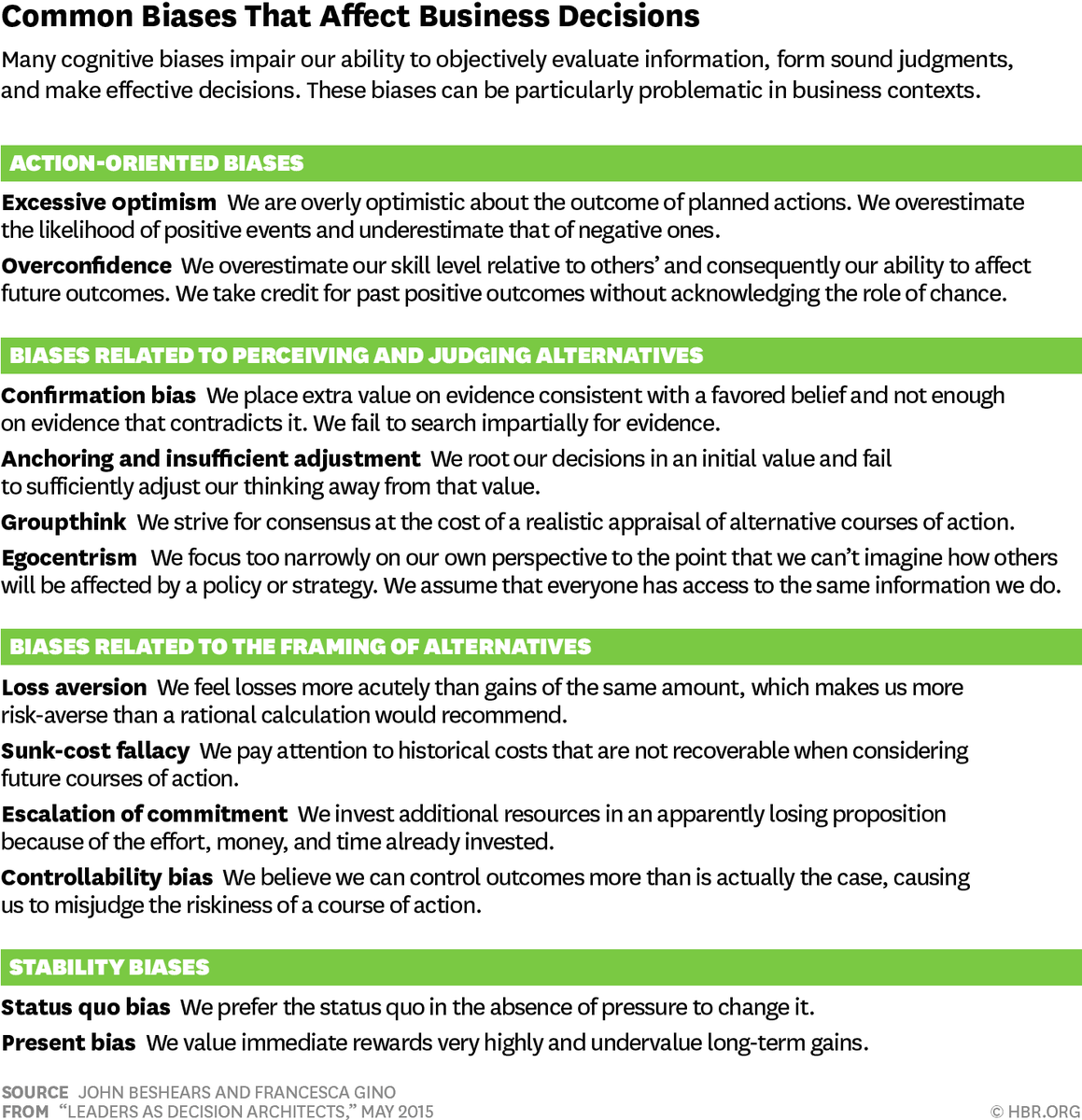

What’s the contrast effect? Well, as with many of the biases, it’s exactly what it sounds like: an effect that occurs because of a comparison. That is, people are more likely to perceive differences that are bigger or smaller because of something they’ve seen first. This is something that is used in sales — all — the — time. If you’re shopping for a new car, the salesperson may show a series of cars that are way out of your price range and then show you one that’s just a little out of your price range. After having seen so many cars that are way out of your price range, the one that’s just a little out of your price range won’t seem that far out of your price range. The contrast effect.

That’s not to pick on folks who sell cars, it can even happen with smaller purchases, shoes, for instances. Let’s say you’re looking for a particular kind of footwear. The salesperson may show you a bunch of shoes that don’t quite fit your needs and happen to be priced rather cheaply. Then, the salesperson shows you a shoe that does fit your needs, but is quite a bit more expensive. As you’ve seen all these shoes that aren’t what you need and now you’ve finally come to one that meets you’re needs, you may ignore the price and buy the shoes.

One of my favourite examples of the contrast effect comes from Dan Ariely‘s book, Predictably Irrational:

One day while browsing the World Wide Web (obviously for work-not just wasting time), I stumbled on the following ad, on the Web site of a magazine, the Economist.

I read these offers one at a time. The first offer-the Internet subscription for $59 seemed reasonable. The second option-the $125 print subscription-seemed a bit expensive, but still reasonable.

But then I read the third option: a print and Internet subscription for $125. I read it twice before my eye ran back to the previous options. Who would want to buy the print option alone, I wondered, when both the Internet and the print subscriptions were offered for the same price? Now, the print- only option may have been a typographical error, but I suspect that the clever people at the Economist‘s London offices (and they are clever-and quite mischievous in a British sort of way) were actually manipulating me. I am pretty certain that they wanted me to skip the Internet- only option (which they assumed would be my choice, since I was reading the advertisement on the Web) and jump to the more expensive option: Internet and print.

But how could they manipulate me? I suspect it’s because the Economist‘s marketing wizards (and I could just picture them in their school ties and blazers) knew something important about human behavior: humans rarely choose things in absolute terms. We don’t have an internal value meter that tells us how much things are worth. Rather, we focus on the relative advantage of one thing over another, and estimate value accordingly. (For instance, we don’t know how much a six- cylinder car is worth, but we can assume it’s more expensive than the four- cylinder model.)

In the case of the Economist, I may not have known whether the Internet- only subscription at $59 was a better deal than the print- only option at $125. But I certainly knew that the print and-Internet option for $125 was better than the print- only option at $125. In fact, you could reasonably deduce that in the combination package, the Internet subscription is free! “It’s a bloody steal-go for it, governor!” I could almost hear them shout from the riverbanks of the Thames. And I have to admit; if I had been inclined to subscribe I probably would have taken the package deal myself. (Later, when I tested the offer on a large number of participants, the vast majority preferred the Internet- and- print deal.)

Before we movie into some of the ways for avoiding the Contrast Effect, I wanted to make it clear that sales isn’t the only place where this bias can creep up on us.  Another good example is in evaluations (be they interviewing job candidates or marking term papers). If one doesn’t have a rubric by which one is scoring candidates (or papers), it can be easy to slip into the contrast effect: “Well, that candidate was much better than the last candidate, let’s put them through to the next round.” It could be that the latter candidate, while better than the first, still doesn’t meet your criteria to make it the next round, so putting them through would be wasting valuable resources — both yours and theirs.

Another good example is in evaluations (be they interviewing job candidates or marking term papers). If one doesn’t have a rubric by which one is scoring candidates (or papers), it can be easy to slip into the contrast effect: “Well, that candidate was much better than the last candidate, let’s put them through to the next round.” It could be that the latter candidate, while better than the first, still doesn’t meet your criteria to make it the next round, so putting them through would be wasting valuable resources — both yours and theirs.

Ways for Avoiding the Contrast Effect

1) Standardized Evaluation

In our most recent case involving interview candidates or term papers, creating a rubric or standardized method of evaluation prior to examining candidates/papers will go a long way to help one avoid falling into the trap of the contrast effect. This method could also be applied when it comes to shopping (i.e. sales). For instance, let’s say you’re looking for a car. Prior to arriving at the dealership, you could create a table for how you’re going to evaluate the cars you view while at the dealership. In this way, you can guard against the salesperson knowingly (or unknowingly) showing you cars at either end of the spectrum before showing you the cars you might actually purchase.

2) Are There Other Options?

Often times, when we’re succumbing to the contrast effect, we’re looking at option A versus option B. This is why it’s so important to have some sort of standardized evaluation (see #1), but short of a standardized evaluation, it’s important to remember that almost never are those two options your only two options. “Should I get this car or that car?” Well actually, you have another option — neither of those cars. And another option, you could consider buying a bike or maybe taking public transportation. Whenever you find yourself faced with a decision between two options, it can be useful to consider other options, just in case you’ve fallen into the trap of the contrast effect.

Note: the images in this post are all examples of the contrast effect.

If you liked this post, you might like one of the other posts in this series: