As I look to breathe some life back into writing, I thought I’d take a quick peek at some of the “drafts” I had saved from when I used to write regularly. Fortunately, there aren’t too many there. In the interest of trying to start fresh, I thought I’d do a quick post addressing some of these ideas kind of in the same way that Wikipedia has stubs.

As I look to breathe some life back into writing, I thought I’d take a quick peek at some of the “drafts” I had saved from when I used to write regularly. Fortunately, there aren’t too many there. In the interest of trying to start fresh, I thought I’d do a quick post addressing some of these ideas kind of in the same way that Wikipedia has stubs.

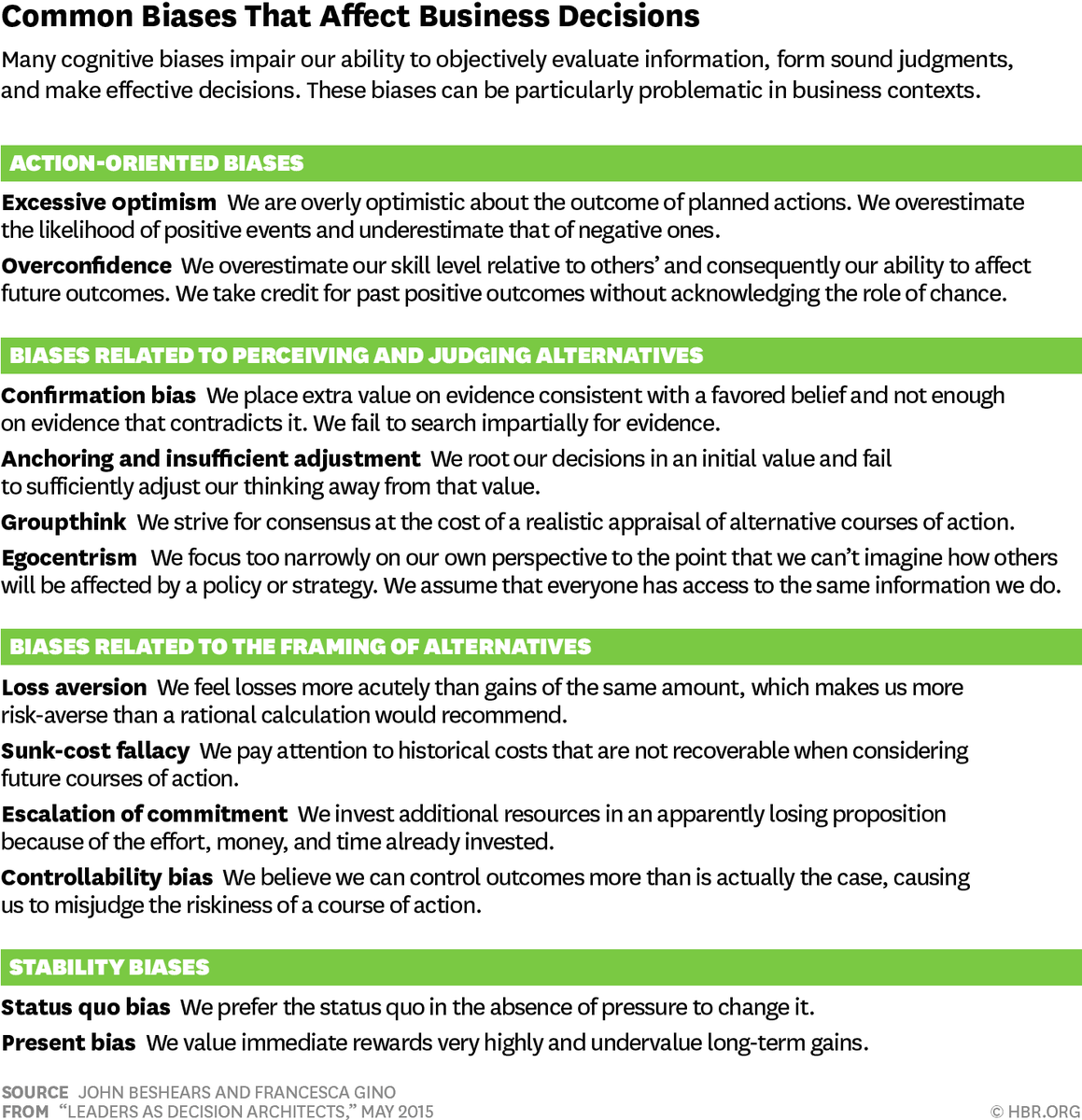

Planning Fallacy: Many years ago, I wrote about the planning fallacy as part of my series on cognitive biases (i.e. how to make decision better). Something I didn’t talk about in that post was the difference between a 7-day and 5-day workweek. Let me explain. For those that go to university, everyday is eligible for a “work” day (i.e. homework). Many things are due on Monday morning and rather than push to complete something on Friday afternoon (or night?), students will often be writing things on Sunday night. Not only am I drawing on my experience as a student, but I’ve been teaching for the last 7+ years and I can say with authority, if I give students a full week (7 days) to complete an assignment and make an assignment due at 1159p on Sunday night, 50%+ of the class will complete that assignment sometime on Sunday. I’m digressing a bit from the point. So, we get used to this “7-day workweek” to complete things. When we move into the work world, that “week” shifts from 7 days to 5 days (and even less in cases of holidays or even less than that if you take into account mandatory meetings, etc.). So, when someone estimates how much time they’ll have to complete a work product, they’re used to (primacy effect?) how they were estimating when they were a student and don’t take into account the ‘truncated’ week.

Science Fiction, Humans, and Aliens: In those sci-fi movies that have some form of alien (i.e. non-human), often times, there’ll be a scene where the humans are kept in a cage. It made me think about how humans keep some animals in cages (i.e. zoo). Maybe to a different species, we (humans) would be treated in the same way we treat animals.

Gendered Language: There was a journal article from a few years ago that caught my eye. Here’s a bit of the abstract:

The language used to describe concepts influences individuals’ cognition, affect, and behavior. A striking example comes from research on gendered language, or words that denote individuals’ gender (e.g., she, woman, daughter). Gendered language contributes to gender biases by making gender salient, treating gender as a binary category, and causing stereotypic views of gender.

Like I said yesterday, if you’ve been following me for any sort of time, this bit about our words having an effect on us shoudn’t come as a surprise. However, this journal article is strong evidence to keep in your pocket if you need to point to something evidence-based in a discussion.

The Problem of Excess: Another good journal article that I’ve been saving for over 5 (!) years. /facepalm. I still remember my first grad school economics course and the professor was explaining the fundamental principle that underlines economics — scarcity. I wanted to raise my hand and disagree on the merits, but it didn’t seem appropriate. I can see and understand how scarcity came to be the dominant theory of the day, but a part of my being just feels that that interpretation is… near-sighted. Seeing this journal article a few years after that class highlighted a different perspective. Here’s a bit of the abstract:

This article argues for a new branch of theory based not on presumptions of scarcity—which are the foundational presumptions of most existing social theory—but on those of excess. […] It then considers and rejects the idea that excess of one thing is simply scarcity of another. It discusses the mechanisms by which excess creates problems, noting three such mechanisms at the individual level (paralysis, habituation, and value contextuality) and two further mechanisms (disruption and misinheritance) at the social level. […] It closes with some brief illustrations of how familiar questions can be recast from terms of scarcity into terms of excess.

Enjoy your weekend!