Hello Hello! It’s been a little more than three weeks since my last post. I’ve finished up the requirements for the MBA, so I should be back to writing posts with some regularity. Since today’s Monday, I thought I’d restart that series of posting about a cognitive bias on Mondays. Today’s cognitive bias: the halo effect.

Hello Hello! It’s been a little more than three weeks since my last post. I’ve finished up the requirements for the MBA, so I should be back to writing posts with some regularity. Since today’s Monday, I thought I’d restart that series of posting about a cognitive bias on Mondays. Today’s cognitive bias: the halo effect.

The halo effect is essentially believing that someone is good at something because they were good at something else. For instance, celebrities are often cited when talking about the halo effect. Many regard celebrities as beautiful and as a result of the halo effect, surmise that these celebrities are also smart (when in fact, this is not always the case).

There’s a famous study about the halo effect from 40 years ago. Here’s an excerpt:

Two different videotaped interviews were staged with the same individual—a college instructor who spoke English with a European accent. In one of the interviews the instructor was warm and friendly, in the other, cold and distant. The subjects who saw the warm instructor rated his appearance, mannerisms, and accent as appealing, whereas those who saw the cold instructor rated these attributes as irritating. These results indicate that global evaluations of a person can induce altered evaluations of the person’s attributes, even when there is sufficient information to allow for independent assessments of them. Furthermore, the subjects were unaware of this influence of global evaluations on ratings of attributes. In fact, the subjects who saw the cold instructor actually believed that the direction of influence was opposite to the true direction. They reported that their dislike of the instructor had no effect on their ratings of his attributes but that their dislike of his attributes had lowered their global evaluations of him.

Ways for Avoiding the Halo Effect

1) Different strengths for different tasks

One of the easiest ways to avoid falling into the trap of the halo effect is to notice that there are different skills/strengths required for different tasks. As such, just because someone is good at climbing mountains doesn’t mean that they would make a good politician. The strengths/skills required for those two tasks are different. Put another way, think about the strengths/skills required for a particular tasks before evaluating whether someone would be good at that task.

2) Notice other strengths (or weaknesses)

It’s been said that, “nobody’s perfect.” When someone is good at one thing, there’s a good chance that they won’t be good at something else. Noticing that this person isn’t good at someone else may help to quell the urge to assume that this person is good at everything.

If you liked this post, you might like one of the other posts in this series:

- Ignore Sunk Costs

- Loss Aversion and the Big Picture

- The Endowment Effect – Yours Isn’t Always Better

- Get a Second Opinion Before You Succumb to the Planning Fallacy

- Perspective and the Framing Effect

- The Confirmation Bias — What Do You Really Know

- Don’t Fall for the Gambler’s Fallacy

- Situations Dictate Behavior

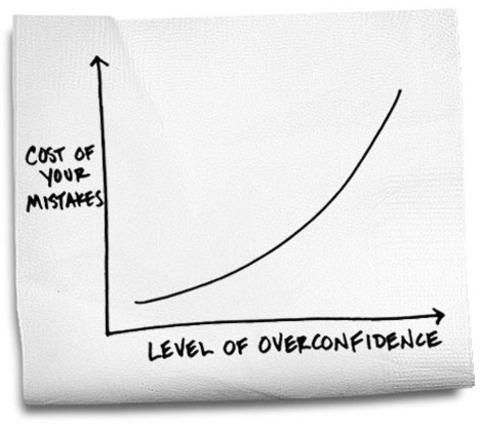

- When 99% Confident Leads to Wrongness 40% of the Time